Jets’ Antonio Cromartie Passes On Lessons Of Frugality

According to Sports Illustrated, 60 percent of NBA players will be broke within five years of retiring. The risk of bankruptcy is even worse in the NFL — 70 percent of players will be broke within two to four year of their retirement from football. Although the athletes often earn millions of dollars in salary and endorsement deals, many quickly fall into habits of spending frivolously and falling prey to freeloaders. Athletes in their prime tend to forget their limited earning potentials. But if they’d simply eliminate their entourages, spend within their means and utilize good accounting, professional athletes could use the money earned during the heights of their careers and be set for life.

According to Sports Illustrated, 60 percent of NBA players will be broke within five years of retiring. The risk of bankruptcy is even worse in the NFL — 70 percent of players will be broke within two to four year of their retirement from football. Although the athletes often earn millions of dollars in salary and endorsement deals, many quickly fall into habits of spending frivolously and falling prey to freeloaders. Athletes in their prime tend to forget their limited earning potentials. But if they’d simply eliminate their entourages, spend within their means and utilize good accounting, professional athletes could use the money earned during the heights of their careers and be set for life.

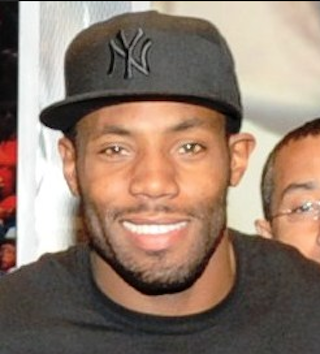

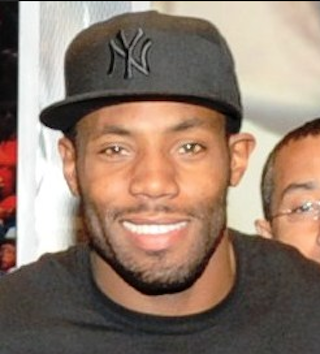

One NFL player is now heeding that advice. Jets Cornerback Antonio Cromartie may have broken Sports Illustrated’s rule of not having almost a dozen baby mamas, but he learned the other lessons the hard way. Newsday’s Bob Glauber recently spoke with Cromartie about his financial transformation.

Cromartie sailed through $5 million within his first two seasons in the NFL. Before he knew it, almost all the money earned during his first season with the San Diego Chargers was gone.

How could anyone blow through that kind of money so quickly? Well, for starters Cromartie has 10 kids by eight women, including two with his wife. But he also bought nine cars, two mansions and gave a ton of jewelry, expensive gifts and cash to friends and family members — many who just popped out of the woodwork after Cromartie’s windfall.

I had two Dodge Chargers, probably spent $100,000 just fixing them up,” he told Glauber. “I had a ’65 Caprice, which I spent $100,000 on. I had two BMWs, two Escalades.”

But Cromartie will not be another Sports Illustrated financial casualty, however, thanks to GSO Business Management’s Jonathan Schwartz. Cromartie’s manager, the late Gary Wichard, recommended his client meet with the Los Angeles CPA for financial advice. Soon, that relationship would change Cromartie’s life.

In Cromartie, Schwartz saw a man with a big heart and an entourage that took advantage of him.

[Cromartie] didn’t surround himself with caring and loving people,” Schwartz told Glauber. “My intention was to show him that there are people who love you for who you are, not for how much you make. When I first met him, I saw a wonderful heart and human being that people were taking advantage of, and I wanted to be a part of seeing his personal growth. Part of that is financial discipline.”

In a program set up by Schwartz, Cromartie’s salary goes straight to the CPA’s office, where Schwartz and his staff pay all his bills and put money into Cromartie’s investments. They also provide their client with a monthly report explaining where the money went, including child-support payments through college for all of his children.

Not only did Cromartie learn not to spend frivolously, Schwartz also taught him how to pinch pennies. In fact, Cromartie spent two weeks in Schwartz’s home with his wife and three children so the athlete could see a settled home environment. Cromartie took many of the financial lessons he learned in that time to heart.

I can tell a lot of things to a lot of clients, but that doesn’t mean they’ll listen and accept what I say and practice that discipline,” Schwartz told Glauber. “[Cro] buys into it. He knows that a professional athlete’s earning period is limited, and that the best form of accumulating wealth is not to spend. His peers will go buy Rolls Royces and Ferraris and diamond jewelry, but 25 years from now, Antonio can still maintain his lifestyle, sit at the beach enjoying a cocktail and say, ‘I’ve earned it.'”

Cromartie now drives a Prius, and refers people asking him for money to Schwartz, who tells them Antonio’s money is “earmarked for other things,” and is not “readily available.” Most of the time, he says, “they don’t call back.”

At his current standard of living, Cromartie’s now fully funded until he’s 100 years old. Plus, his earnings will grow to multi-generational levels, so his family will never worry about money.

Cromartie now uses the lessons he learned from Schwartz to mentor younger players. The 29-year-old has taken on a leadership role in the Jets’ locker room, helping others avoid what he did wrong in the beginning.

I tell the young guys, ‘Don’t spend any money the first year and a half of your career,’” Cromartie told Glauber. “You don’t know what will happen after that. You might be released. You might be hurt. Just save your money.”